Kate Randell, Director Infrastructure Advisory at PwC and Tom Barclay, Director Real Estate Advisory at PwC and one of our valued Property Council South Island Regional Committee members, share their views on turning housing aspirations into reality.

Introduction

The recent Government announcement of Pillar One of the ‘Going for Housing Growth’ programme marks a significant step towards increasing land availability for urban development by removing planning barriers, particularly in our larger Territorial Authorities. The Pillar One initiative, along with future pillars addressing infrastructure funding and financing, aims to enable cities to expand both upwards and outwards with the support of infrastructure investment.

Together with wider housing reform, including amendments to the Resource Management Act, Building Act, Overseas Investment Act and tax regime for residential investors, there is the potential to materially shift the dial on housing supply long term.

However, as a small country with limited private and public capital, New Zealand faces unique challenges in accelerating housing supply, particularly the infrastructure required to unlock new supply, of the right type, in the right locations. Effective collaboration between the Government and the housing sector is essential to align investment, policies, and tools, particularly those related to infrastructure to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

In an ideal world, new development would be weighted towards brownfield rather than greenfield areas to make better use of our existing resources and infrastructure and preserve our productive land. However, growth in both areas is clearly needed given New Zealand is playing years of catch up on housing supply.

This article explores the complexities and tradeoffs involved in managing both brownfield and greenfield development (growing ‘up’ and ‘out’). It also examines short-term market feasibility challenges, specifically for vertical development, and proposes strategies to incentivise developing ‘up’ in a market when there is increasing opportunity and incentive to develop ‘out’.

How can we ensure that the New Zealand housing market continues to grow ‘up’ when there is increasing opportunity and incentive to grow ‘out’?

Infrastructure challenges – unlocking vertical housing supply by delivering the right solutions, in the right place, at the right time

The lack of certainty about investment in urban infrastructure places a cap on development within our cities. The planned infrastructure pipeline will help give the market certainty provided the type and location of infrastructure identified (and any subsequent City deals assuming they come second) reflects where the greatest development opportunities lie.

To realise a return on infrastructure investment, the development community must be involved in shaping the pipeline. This offers numerous benefits, including leveraging their market understanding, technical expertise, and financial resources to inform realistic and efficient urban strategies.

Shared vision and constructive dialogue between Crown, Councils, iwi and the development community allows for the development of flexible and adaptable strategies that can respond to changing market conditions and emerging challenges. This agility is key to maintaining a robust land supply pipeline.

This approach has been successfully implemented overseas including via shared governance models in London (e.g. London’ Kings Cross and Vauxhall/Battersea/Nine Elms), Barangaroo in Sydney and locally albeit to a lesser extent (e.g. the Kainga Ora Large Scale Projects and Christchurch Earthquake Rebuild).

Who, and how, we pay for infrastructure is a stickier point to resolve, particularly in high growth towns and cities. The proposed shift to a user pays (or ‘growth pays for growth model’) has strong potential however it will have to carefully balance the amount a ‘user’ pays (and when they start paying) with the benefit that user receives.

There are a lot of moving parts in the housing system and land supply policy announcements have been made ahead of more detail around infrastructure funding presenting some short-term challenges. Developers may purchase land in areas without planned infrastructure, risking underestimation of development costs or they may hold off or shelve existing plans until there is greater certainty (negatively impacting supply when market conditions do start to improve).

Alternatively, there could be challenges to the growth charges, forcing the Government and Councils to choose between spending to unlock housing or further restricting supply. Both are politically unappealing outcomes, as recently witnessed in Drury.

Embedding the true cost of infrastructure into land values ensures that the financial burden of public investment is equitably shared by those who benefit directly from increased land values. This approach incentivises efficient land use in most instances as the true cost of enabling greenfield development is higher. This should improve the relative attractiveness of brownfield development.

Value capture mechanisms offer Councils the opportunity to direct growth into desired areas, encouraging integrated land use and infrastructure planning to support new developments with essential services and amenities. This approach works best in high-potential areas, reducing urban sprawl and enhancing livability.

Effective design of value capture mechanisms should balance cost certainty for the market with flexible application across different precincts, towns, and cities, similar to the UK’s s106 mechanism. This allows for bespoke agreements between developers and Councils and has been reasonably successful in redistribution of cost and benefit across high growth areas.

Incentivising vertical development – giving developers a reason to build up

Rationally, if infrastructure is available (or can be made available), greenfield development (building ‘out’) will be prioritised by developers. This is typically less complex, lower density and in most instances, lower risk. It is quicker to develop and less reliant on presales.

For example, in the aftermath of the 2010 / 2011 Christchurch earthquakes, mass greenfield rezoning occurred in the neighbouring Selwyn District (Rolleston, Lincoln and Prebbleton townships) and the Waimakariri District (Rangiora and Kaiapoi townships).

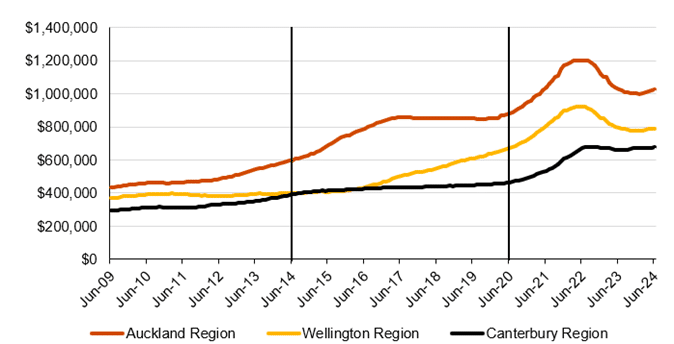

There was an initial rise in prices due to the housing shortage caused by the red zoning of some properties and extensive repair programmes requiring short-term accommodation. However, the subsequent increase in residential land supply in neighbouring districts and a number of new developments in the city itself effectively kept the median sale price in the region relatively flat between 2014 and 2020. Over the same timeframe, prices in the Auckland and Wellington regions saw significant increases as shown in the chart below.

While a positive outcome in terms of affordability, it was not without tradeoffs, including the loss of productive land, the marginal costs of infrastructure, the ‘hollowing out’ of the city and the reliance on private vehicles and new motorways for commuting from the neighbouring districts. The primary type of housing developed was single level standalone homes, which require the most land.

Chart: Median sale prices in the Auckland, Wellington and Canterbury Regions 2009 – 2024

Source: REINZ

Planning, demand and development economics at the time all supported this type of development and when given the option between a three bedroom standalone home (albeit a 25-minute drive from the city) or a two bedroom CBD apartment for a similar price, people voted with their feet (or perhaps more accurately, their cars).

From 2020 onwards, Christchurch has seen more densification, including a proliferation of terrace housing around the city and mid-rise apartment development in the CBD. Standalone housing has become more expensive and development economics for higher density typologies has improved (also driven by delivery of most of the CBD blueprint) meaning the balance has shifted back to a mix of both ‘up and out’ development.

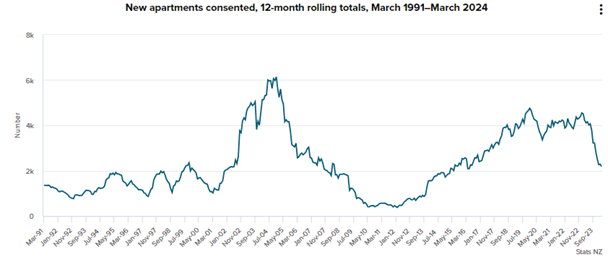

In the current market across the country, few scale apartment developments (i.e >6 storeys) are commercially feasible. The view on risk associated with these developments by financiers is high. This trend is playing out through a significant dropoff in apartment consenting and development activity.

There are developers that specialise in apartments and will continue to build regardless of what stage of the property cycle we are in, but these parties (including build-to rent (BTR) developers) tend to be the exception, rather than the rule. Interest rates, access to development finance, construction costs and presales (particularly for vertical development) are likely to continue to be barriers to unlocking housing growth in the short term.

Given this context, the key question is to what extent do the Government and Councils wish to support (or incentivise) density (building ‘up’) through the cycle vs leaving the market respond with density when it is feasible?

If we assume that building ‘up’ remains desirable in terms of the outcomes it drives, but is less attractive from a feasibility perspective through a significant part of each property cycle, what tools exist to support the vertical market?

Some examples could include:

- Continuing to leverage Crown and Council land ownership to procure higher density housing outcomes, focusing in particular on existing public housing developments, proximity to transport and city centres.

- Fasttrack resource and building consents for higher density developments in target growth locations.

- Supporting the growth of the BTR market. BTR is attractive from a counter cyclical perspective given it is not reliant on presales. These are scale developments that comprise long-term rental accommodation and can materially change supply dynamics in micro markets. Proposed changes to the Overseas Investment Act (OIA) to support offshore investment in (and the liquidity of) the BTR market are positive. Further changes to align the tax regime with the retirement and student accommodation sectors in New Zealand and offshore markets like Australia (which we are competing with for capital) would further support building ‘up’.

- Relaxing regulations for apartment development – this is already being addressed to some extent through the removal of minimum floor areas and balcony requirements and the proposed requirement for some Councils to enable more mixed use developments.

- First home buyer support for apartments. While the first home buyer grant has been removed, this could be refocused to apartments, which might help to support presales and feasibility for such developments. Interestingly, Fletcher Living is offering $10,000 to first home buyers within its developments in Auckland and Canterbury.

- Similarly, Government or Council underwrites (availability payments) for public and affordable housing as part mixed tenure vertical developments could assist feasibility through cycles and help to address the supply of both affordable and market rental accommodation. The Victorian State Government in Australia recently completed a pilot for a BOT (build, own, transfer) style ground lease model based on these principles. This is another approach for leveraging Crown / Council land and / or redeveloping existing estates.

- Lower the loan-to-value ratios and / or debt-to-income ratios for apartment buyers to make these typologies relatively more easy to purchase than other housing typologies (this would have a compounding effect given apartments, in most instances, have a lower entry price than terrace and standalone homes). We have already come a long way in this area, noting that until as recently as 2021, some banks required a 50% deposit for apartments smaller than 45 sqm.

- Consider a change to a land value rating system which would be advantageous to apartment owners. Rates in most New Zealand cities are struck based on capital values (the value of the land and buildings). Because most apartment developments reflect a high ratio of homes to underlying land area, striking rates based on the value of the underlying land, rather than the value of each individual apartment, could help to lower the rates burden for apartment owners as well as encourage more efficient use of land.

Conclusion

Ultimately, increasing housing supply at this point in the cycle is likely to be more dependent on lower interest rates than on increasing land supply or funding urban infrastructure. However, we must not ignore these long-term structural issues that have plagued our housing market for decades. The Going for Housing Growth initiatives, especially the land supply element, should help cap (and potentially reduce) land prices over time, which will assist affordability.

Given the scale of New Zealand’s housing problem, a suite of responses is needed, including incentives and regulations supporting both brownfield and greenfield development, along with targeted capital investment in infrastructure. While we need both, we must decide whether to focus our finite capital more on brownfield density or new greenfield options; each of our major Councils is likely to have a differing political view on what is optimal for their local market.

With cyclically high interest rates currently hindering home buyers, investors and developers, there is a risk of significant demand pressure as rates start to decrease. When the market inevitably turns, Councils and developers need the right tools in place to provide the necessary supply response and avoid a rinse-repeat of the boom-bust cycle we are currently navigating.

Authors

Tom Barclay

Director, Real Estate Advisory

PwC

Tom’s work spans financial modelling, development feasibility analysis, due diligence and business cases for PwC’s clients nationally. His recent work has focused on urban regeneration and housing projects. Tom is a born and bred Cantabrian. After five years in Auckland, he moved home to Christchurch in 2021 to help establish PwC’s Real Estate Advisory team in the South Island.

Kate Randell

Director, Infrastructure Advisory

PwC

Kate recently joined PwC’s Infrastructure Advisory team as a Director, based in Auckland. She has a background in planning and is passionate about creating high-quality, sustainable places to live, work, and play. Kate has been lucky enough to work on several large-scale multi phased regeneration projects, and infrastructure projects in New Zealand and UK including Auckland Light Rail, the Battersea Power Station redevelopment and the Avon River Precinct.