Property Council’s South Island Regional Committee member, Tom Barclay of PwC shares his view on the move to smaller homes in Aotearoa.

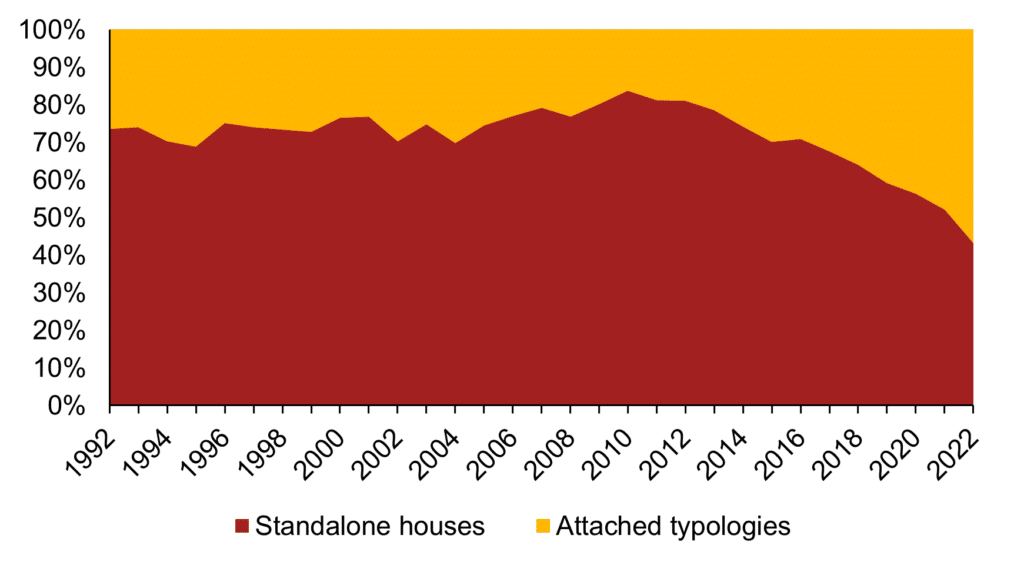

2022 was the first year in New Zealand’s history where more attached than standalone homes were consented. This milestone has been a long time in the making. It marks our changing culture, and national psyche, when it comes to how, and where, people are living – particularly in our largest cities.

Chart 1: Attached* vs standalone home consents 1992 - 2022

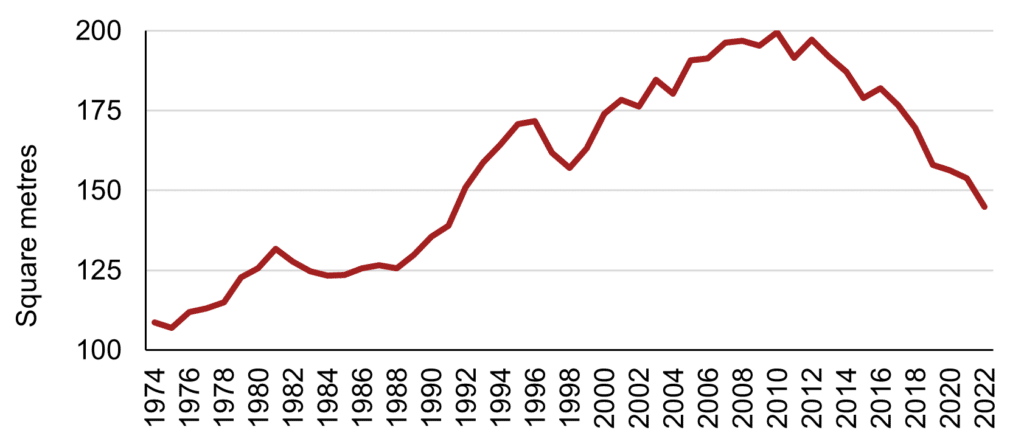

As attached homes are typically smaller in floor area than standalone homes, it follows that the average size of the houses we are building is decreasing. After reaching peak “McMansion” in the 2000’s at around 200 square metres, the size of the average new kiwi home declined to around 145 sqm in 2022 (albeit this is still well above the c. 110 square metres that was typical in the mid-1970s).

Chart 2: Change in the average floor area of residential houses consented in New Zealand 1974-2022

What’s driving the move to smaller homes?

In part, the trend towards smaller, attached housing has been enabled by planning measures targeting improved urban outcomes through density, proximity to (and more frequent use of) public transport and social infrastructure, and lower emissions (think the Auckland Unitary Plan of 2016).

Over the course of the current market cycle (which has passed it peak), I believe the rapid decrease in the average house size consented (an approximately 30% reduction in about 15 years) has largely been a response to the affordability crisis. While typically costing more on a dollar per square metre basis to construct, smaller homes cost less overall and require less land per unit (the flipside of this is that higher density homes place disproportionate demand on infrastructure, which has not been developed at the same rate).

Economies of scale

Whether it is the emergence of suburban apartments in Auckland, the ’walk-ups’ of Wellington or the ‘two-bed-townhouses’ that have dominated the Christchurch development market in recent years, the economics of these typologies have, until recently, been favourable in terms of both price points for purchasers and profitability for developers. This is a rare ’win-win’ in the housing market. Although, even with a significant increase in the number of ’small’ homes being consented and developed, records for median house prices (including apartment prices per square metre) continued to be broken through to the end 2021. This highlights the scale of this last ‘boom’ cycle where we were also consenting the highest number of homes since the 1970s (c. 49,000 p.a. in 2021 and in 2022).

While the benefits of density in urban centres are well established – reflecting a better use of our limited resources (primarily land but also public transport and horizontal infrastructure) – many still question the merits (or point out the limitations) of living in smaller homes. This isn’t just our older generations, who reminisce about a time where the kids and dogs had more room to run around, it also includes my generation (millennials), who grew up in such homes and often feel they have been priced out of the opportunities their parents and grandparents enjoyed at the same age.

That said, reverting to housing affordability levels of the past will require real wage growth beyond the realms of what seems possible, or a decrease in house prices that would put the entire financial system at risk. Those matters aside, building more smaller homes in locations with high levels of amenity (including high quality public realm, green spaces and access to great public transport) seems to be one of the best options we have for addressing a multitude of challenges including affordability, commute times, carbon footprint and emissions.

Where to next for the average kiwi home?

Density is now being rolled out nationally through:

- The National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD) which allows for development of six storeys within walkable catchments of rapid transit stops for the larger local authorities.

- The Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2021 which requires many local authorities to apply medium density residential standards (MDRS). The standards mean that up to three dwellings of up to three storeys can be developed on a property without needing to apply for resource consent.

Both these policies are highly relevant to the future of housing development in my hometown, Christchurch, where in the same week at the end of February:

- a proposed route for a new rapid transit service was put out for consultation (where development around key stops would be enabled for up to six storeys) and;

- the Christchurch City Council sought to exempt almost half the city’s residential properties from the new MDRS standards through Plan Change 14.

While all the signs point to a continuation in the development of smaller homes as both a planning and affordability response, 2023 will see some significant challenges for developers of higher density housing including increasing construction and debt costs while property prices are expected to continue falling (at least in the short term).

Longer term, a key challenge for the supply of higher density housing in New Zealand, particularly in brownfield (i.e. infill) locations will be infrastructure capacity (three waters, roading etc). The ability of local authorities to fund the infrastructure upgrades required to supply the density of housing sought by central government (and provide resilience to, for example, future weather-related events) is a consideration that goes beyond the scope of this article but is perhaps the biggest challenge facing New Zealand in 2020s.

This all plays into housing affordability and ultimately, housing choice. While it’s true that real wages have been rising and house prices have been falling (which is good for first home buyers, who currently make up a record proportion of the buyer market), the facts are that based on transaction volumes, the overall buyer pool is a lot smaller than in recent years, the cost of debt has significantly increased and most house prices are still well above pre-Covid levels. Our housing affordability issues significantly predated the pandemic.

Interestingly, a recent Stuff Now Next survey suggested that 61% of renters want to own a home, but they cannot afford to buy. But perhaps more interesting is that of the 61%, the vast majority (79%) wanted to buy a house (as opposed to a townhouse, unit or apartment). However, the reality of housing aspirations vs affordability continues to play out in the data and the longer-term trend towards smaller attached homes looks set to continue.

That said, 2023 might be the best opportunity for first home buyers to enter the market that we have seen in recent years, and perhaps, for some, the trade-off between price and the pavlova paradise of the past might be less pronounced.

Tom Barclay

Director, Real Estate Advisory | PwC

Tom’s work spans financial modelling, development feasibility analysis, due diligence and business cases for PwC’s clients nationally. His recent work has focused on urban regeneration and housing projects. Tom is a born and bred Cantabrian. After five years in Auckland he moved home to Christchurch in 2021 to help establish PwC’s Real Estate Advisory team in the South Island.